|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The “doubled die” variety is one of the most popular die varieties for collectors. Because doubled dies are so popular, there is a lot of information out there about these varieties and they are often seen for sale on internet auction sites such as Ebay. Unfortunately, not all of the information out there is correct. A frequent misconception about doubled dies is that they are produced when coins are struck twice by the dies. This is definitely not the case. All U.S. coins made for circulation are only struck once unless there is a mishap in the coining press. Even then, the resulting error coins will NOT be doubled dies. Only proof coins are struck more than once with the number of times that they are struck depending on the alloy of the planchets that will be struck into coins. But even here, the number of times that a proof coin is struck will have no bearing on whether or not a doubled die is produced. The key to doubled dies lies in the name – doubled die! As we have seen, coins are struck by steel rods that bear the design images for the coins that they will be striking. These steel rods are called dies. For a doubled die coin to be produced, the doubled image must be on the die itself, hence the term “doubled die.” Doubled dies occur when there are mishaps in making the dies that will be used to strike the coins. On the “How Dies Are Made” page of this website we saw that for most of the Mint’s die making history the master design for a coin was transferred to a Master Hub in a reduction lathe. These have recently been replaced by CNC (computer numerical control) milling machines, but the principal is still the same. The master hub is then used in a hubbing press to create Master Dies. The master dies are used in a hubbing press to create Working Hubs, and the working hubs are then used in a hubbing press to create Working Dies. It is the working dies that are then used to strike the coins in the coining presses. In the Wexler Die Variety Files we define “doubled die” doubling as doubling produced on hubs or dies as a result of a misalignment of the images on the hub and die at some point during the hubbing process. A more accurate term would be “hubbing doubling,” but the term “doubled die” is clearly fixed in our culture and here to stay. The misalignment of the design images may have been when the master hub was squeezing an image onto a master die, when a master die was squeezing an image onto a working hub, or when a working hub was squeezing an image onto a working die. Just where the doubling occurs in this sequence will dictate how common the doubling will be, and that will affect the subsequent values for the doubled coins that are ultimately produced. Doubling can also occur in the process of transferring the design from the galvano to the master hub. Links are provided here to get more details on the doubled master hubs, the doubled master dies, and the doubled working hubs. Doubled Master Hubs – Reduction Lathe Doubling Since the vast majority of doubled die varieties that are reported to us are on coins from doubled working dies, that is where we will focus our attention here. Because of changes in Mint technology for making hubs and dies, the process of making a working die can be divided into two eras. These would be the multiple-squeeze hubbing era and the single-squeeze hubbing era.

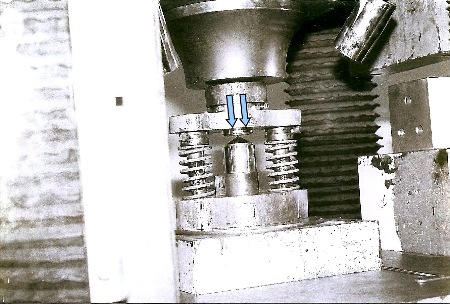

Prior to the use of single-squeeze hubbing presses which could impress the complete design with a single-squeeze (hubbing), the working dies were made in multiple-squeeze hubbing presses. For the first hubbing a die blank was placed on the bottom of the hubbing chamber. A working hub was locked into the top of the hubbing chamber directly above the die blank.

Here we see the hubbing chamber of a multiple-squeeze hubbing press. Arrows point to the working hub which is locked into the top of the hubbing chamber. A die blank with the cone-shaped die face is positioned directly below the working hub. This photo is courtesy of Arnold Margolis and Error Trends Coin Magazine. When the press was activated the working hub was lowered into the die blank with hundreds of tons of pressure. The multiple-squeeze hubbing presses did not allow a deep enough penetration into the working die to make a satisfactory impression in the working die with just one hubbing. The working die had to be removed from the hubbing press and taken to an annealing oven where it was heat treated to relax the molecular structure and “soften” the working die so that it could receive another impression from the working hub.

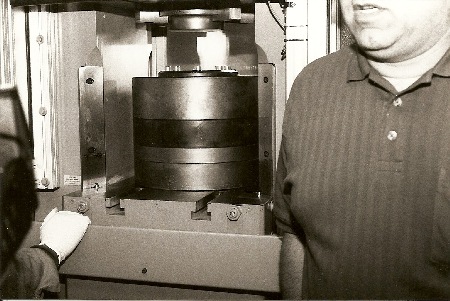

This is an annealing oven that was in use at the Philadelphia Mint during a Coin World sponsored tour of the Philadelphia Mint in 1998. When the annealing process was completed, the working die was returned to the hubbing press to receive the next impression. For the second (and later) hubbings the set-up in the hubbing press was different than that used for the first hubbing. The working die was positioned on the bottom of the hubbing chamber with the working hub sitting directly on top of it. When activated, the top of the hubbing chamber lowered and again squeezed the working hub into the working die.

This photo shows a working die (bottom) and a working hub (top) positioned in the hubbing press for the second hubbing. If additional hubbings were needed, the set-up between the hub and die in the hubbing press was the same. This photo is courtesy of Arnold Margolis and Error Trends Coin Magazine. The hubbing and annealing processes were repeated until it was determined that a satisfactory image was on the working die. For some of the larger denominations it may have taken as many as nine or ten hubbings to leave a satisfactory image on the working die. Since the working hub and working die were placed into the hubbing chamber manually, there was the possibility that the working hub would not be placed on top of the working die accurately. If there was any kind of misalignment of images between the working hub and the partially completed working die, doubled images would appear on the working die wherever these misalignments occurred. At this point a “doubled die” was born and if that doubled die was put into use to strike coins, all coins struck by that die would show exactly the same doubling. After the production of the famous 1955 Lincoln cent Die #1 doubled die variety with an extremely strong spread to the doubling, the Mint took measures to prevent such widespread doubled dies from ever happening again. They placed lugs around the rim of the dies and hubs so that the images on the hub and partially completed working die would align properly when they were placed in the hubbing chamber. These lugs were raised on the working die and they were depressed indentations on the working hub.

This photo illustrates a working hub that was created for the Lincoln cent reverse. If you look carefully, you can see that the images on the face of the working hub are raised and look just like they will appear on the struck coins. The arrows point to grooves along the edge of the hub. The lugs on the working die will fit into these grooves to allow proper alignment of the working hub and the working die when more than one hubbing is needed to complete a satisfactory image on the hub or die being made.

This is a working die (left) for the reverse of the Lincoln cent as it appears after being hubbed. Notice that the design is reversed from what you will see on the struck coins. Though difficult to see in the photo, the design is depressed (incuse) in the working die. Arrows point to the raised areas (lugs) around the rim that align to the grooves of the working hub. To the right of the working die we can see some more blank steel rods that can be used to make master dies, working hubs, or working dies. In 1969 the Mint modified the obverse design for the Lincoln cent. As a result of those changes, they experienced difficulty in getting satisfactory impressions in the working dies. To remedy the problem they removed the lugs from the hubs and dies to allow for deeper penetration of the hub into the die. This did fix the problem and allowed the deeper penetration of the hub into the die, but it opened up the possibility of doubled dies again being created with strong spreads. It didn’t take long for the consequences of this decision to be felt. In 1969 a major doubled die was produced for the 1969-S Lincoln cents. Another major doubled die was produced for the 1970-S Lincoln cents. Several doubled dies found their way into production for the 1971 Lincoln cents with two major varieties known for the 1971-S proof cents. The dam broke in 1972 and several doubled die varieties were produced for the Lincoln cents from all three Mints including a major doubled die for the obverse of the P-Mint cents. During this period of time significant doubled dies were being produced for other denominations as well. After the flood of doubled die varieties in 1972 and all of the publicity that they generated, the Mint returned to the practice of placing the lugs around the hubs and dies. Over the years it has been found that different types of misalignments between the images on the hub and the images on the die could occur. The various types of misalignments produced unique characteristics to the doubling found on the dies. Each identifiable type of misalignment of images produced one the “classes” of doubled die varieties. All but one of the leading die variety attributers recognize eight distinct classes of doubled die varieties. Coppercoins also uses a Class IX for doubled die varieties produced on the new single-squeeze hubbing presses. All of the other attributers feel that the doubled die varieties produced on the single-squeeze hubbing presses still fit into one of the eight previously existing classes of doubled die varieties. We have provided links to take you to separate pages for the eight classes of doubled die doubling. Each page will explain the causes and characteristics of one of the classes of doubled die doubling as well as provide you with photo illustrations of doubled dies from that class. For more information on the various classes of doubled die varieties you can click on the following links:

When the Mint introduced the single-squeeze hubbing presses on a trial basis around 1985, and then to produce working dies at Denver and Philadelphia in 1996 and 1997, it had hoped to eliminate doubling produced during the hubbing process. Unfortunately for the Mint, this did not result and minor doubled dies are actually being produced more frequently on the new single-squeeze hubbing presses than they were on the older multiple-squeeze hubbing presses. We believe that we know the reason for this. In the older multiple-squeeze hubbing presses the hub was fixed to the top of the hubbing chamber for the first hubbing. When it descended down into the face of the die it couldn’t move as it made contact with the die as it was locked into the top of the hubbing chamber. In the single-squeeze hubbing presses the set up is different. The die blank is placed into the well of a collar placed in the bottom of the hubbing chamber. The hub is also placed into the well of the collar so that the face of the hub is resting on the conical point of the top of the die blank. Since the diameter of the well in the collar has to exceed the diameter of the die blank and the hub (so that the die blank and hub can be inserted into and removed from the collar, and so that the hub can be pushed downward into the die), there is “play” in the collar well. It allows for some horizontal movement between the hub and the die when the hubbing process begins. There is even the possibility of some rotational movement. It also allows for the hub to be tilted with respect to the die prior to the start of the hubbing since it is sitting unrestrained on top of the die blank in the collar well. Since the hub is slightly tilted at the time the hubbing begins, as it is pushed down into the collar well and into the die blank it will be forced into a more vertical alignment in the collar well. If there is some resistance to the vertical realignment when the hubbing begins, it may snap back into proper alignment at some point as the hubbing proceeds. Hubbing press operators have described a “clunking sound” that is heard when the hub snaps back into proper alignment. When this happens, there will be a misalignment between the image formed prior to the hub snapping into alignment and the image formed after the snap. The result is doubling. Because the hub is not fixed to the top of the hubbing chamber as it was in the multiple-squeeze hubbing presses, the movements resulting from the “play” in the well of the hubbing chamber seem to occur frequently producing minor doubled dies.

This is a photo of a single-squeeze hubbing press in use at the Philadelphia Mint in 1998.

The hubbing press operator is placing one of the collars into the hubbing press. The die blank and working hub will be manually placed into the well of the collar prior to that start of the hubbing. The working die will be inserted first with the cone-shaped top pointing upward and the working hub will sit on top of it with the design resting on the tip of the working die’s cone. Because of how these doubled dies are being produced, the affected area tends to be the center of the die. That is due to the fact that the point of the conical top of the die blank is the first contact point with the hub and it usually doesn’t take very long into the hubbing for the hub to snap or move into a more proper vertical alignment. While the entire obverse and reverse should always be examined carefully, the most likely place to find doubling on dies produced on the single-squeeze hubbing presses is at the center of the die (coin). On October 1, 2009 I had the privilege of having a telephone conversation with George Shue, Senior Advisor in Manufacturing at the U.S. Mint. During this conversation the 2009-D Washington D.C. quarter with a major doubled die reverse came up. Mr. Shue noted that the Mint was aware of this doubled die error and how it occurred. This particular doubled die resulted when a hubbing press operator stopped one of the single-squeeze hubbing presses to realign the hub and die and then restarted the hubbing sequence. In the process a rotational misalignment of images resulted. Mr. Shue further noted that the Mint was able to reproduce the error in a test to see what caused the doubled image originally. The conversation further revealed that the Mint was aware that even though it was contrary to policy, hubbing press operators were taking it upon themselves to sometimes stop the single-squeeze hubbing presses before the hubbing was completed to make adjustments, and then restarting the press to complete the hubbing. To prevent doubled dies like the major variety seen on the 2009-D Washington D.C. quarter from happening again, the Mint has installed “locks” on the hubbing presses. Now if a hubbing press operator stops the press before the hubbing is completed, they will be unable to restart the press until a supervisor comes to inspect everything to make sure that things are reset properly. The supervisor will then “unlock” the press so that the hubbing can be completed. So for now doubled dies continue to be produced despite Mint efforts to eliminate the die variety.

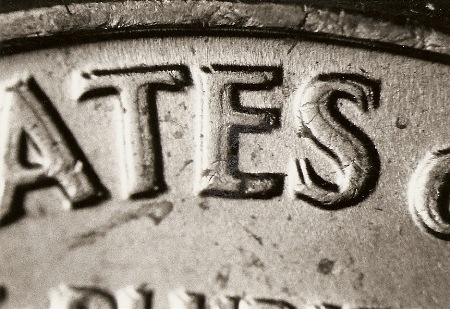

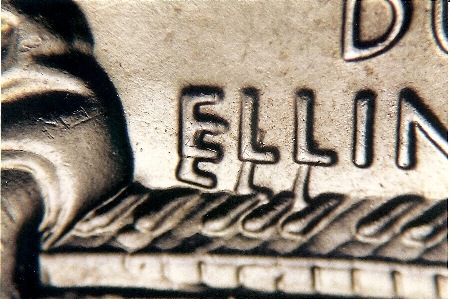

Because of the manner in which the dies receive doubled images through the hubbing process, it is important to realize that doubling seen on doubled dies will be seen as raised and rounded secondary images, just like the normal images on the coin. Doubled letters will often show “splits” in the serifs of the letters whenever the letters have serifs. If the letters have squared off corners, those corners will often show strong “notches”. The separation between the doubled design images is referred to as the spread of the doubling. The spread of the doubling can be very wide or it can be extremely close.

The doubling seen here is on the 1972 Lincoln cent doubled die variety that we have listed as 1972 1¢ WDDO-003. Notice that the doubled images are raised and rounded just like the normal letters in the word GOD.

This doubling is on the word PLURIBUS on the reverse of a 1962 Jefferson nickel that we have listed as 1962 5¢ WDDR-041. Note the strong "split serifs" at the tops and bottoms of most of the letters.

Strong split serifs show at the top and bottom of the 2nd S in STATES. Also note the strong "notches" at the top corners of the T and E. This doubling is on the reverse of a 1964 Lincoln cent that we have listed as 1964 1¢ WDDR-001. For collectors just starting to collect doubled die varieties it is important to know that there are other forms of doubling that can be found on coins that are not the product of a doubled die. These other forms of doubling may have ended up on the coin when it was struck in the coining press, or it may appear on the dies themselves but not as a result of design transfer in the hubbing presses. If you have already done so, we strongly urge you to read the Worthless Doubling page on this website. It explains how these other common forms of doubling are produced and illustrates them with comparisons to examples of genuine doubled dies so that you can learn to tell the difference between the worthless doubling and the genuine doubled dies. To go to the Worthless Doubling page, click here: Worthless Doubling

In the Wexler Doubled Die Files we also classify doubled die varieties as Major, Very Significant, Significant, Minor or Very Minor doubled die varieties. The chief factors in determining which of these categories apply would be the amount of spread to the doubling and/or the amount of doubling. The two usually go hand-in-hand, but there are always exceptions. Sometimes dealer and collector acceptance of a variety also influences the category into which a doubled die will fall. Major Doubled Die Varieties: These are the “big boys.” The two most important factors are the amount of doubling and/or the strength to the spread of the doubling. In a number of cases the doubling is actually visible to the naked eye. The 1955 doubled die Lincoln cent listed as Obverse Die #1 is without doubt a major doubled die variety. It is the undisputed “king” of the Lincoln cent doubled die varieties. The images are very widely spread and almost all design details on the obverse show the doubling. On the other hand, the 1984 Lincoln cent listed as Obverse Die #1 is also considered to be a “major” doubled die variety. However, on this variety there is no doubling on any of the letters around the rim, no doubling to LIBERTY, and no doubling to the date. The doubling is confined to Lincoln’s ear and beard. The doubled details are very widely spread, but to a limited area so it is clearly a case where you don’t need wide separation and a large amount of doubling to be classified as a major doubled die variety.

This is the date on the "King" of the Lincoln cent doubled dies." It is the 1955 Lincoln cent doubled die listed as Obverse Die #1 or 1955 1¢ WDDO-001. This is clearly a "major" doubled die variety.

The 2009-D Washington D.C. quarter with the doubled die listed as 2009-D 25¢ DC WDDR-001 has been recognized in the hobby as a major doubled die variety. While the entire reverse is not affected, the doubled area at the center of the reverse is extremely strong. Very Significant Doubled Die Varieties: These are varieties that come very close to being major doubled die varieties. They typically have strong spreads to the doubling and/or significant amounts of doubling. They would make nice additions to any doubled die collection. Sometimes they are not classified as major doubled dies because they are overshadowed by another doubled die for the same date and denomination. An example of this would be the 1972 Lincoln cent doubled die listed as Obverse Die #2. On any other date this would be a major doubled die variety, however, because of the major Obverse Die #1 few consider Obverse Die #2 to be a major doubled die variety.

This strong doubling is on the obverse of the 1972 Lincoln cent doubled die variety listed as 1972 1¢ WDDO-002. On any other date this would probably be considered a major doubled die variety, but because of the popularity of the even stronger Obverse Die #1 it is greatly overshadowed and considered to be a "very significant" doubled die variety.

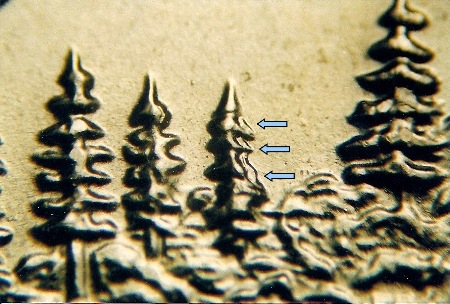

The "extra tree" seen on the reverse of 2005-P 25¢ MN WDDR-001 is bold and widely separated. It has not been touted as a major doubled die variety, but certainly qualifies as a very significant variety.

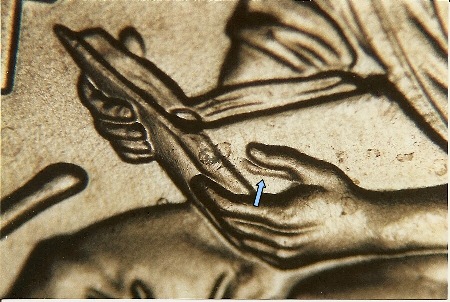

The bold "extra finger" seen on 2009 1¢ FY WDDR-006 certainly qualifies as a very significant doubled die variety. Significant Doubled Die Varieties: These doubled die varieties still have nice spreads and/or significant amounts of doubling. They should be relatively easy to spot when you know where to look for the doubling and are worthy of being included in most doubled die collections. Those who collect only the “easy to see” varieties may exclude these from their collections.

This is doubling on the obverse of 1972 1¢ WDDO-004. The spread of the doubling is much less than that seen on 1972 1¢ WDDO-002, but it is still considered to be "significant" doubling as it is relatively easy to see with low magnification.

The strong doubling on the right side of the target tree on the reverse of the Minnesota State quarter doubled die reverse listed as 2005-P 25¢ MN WDDR-003 qualifies as a significant doubled die variety in the Wexler Doubled Die Files.

This nicely doubled thumb on 2009 1¢ FY WDDR-016 qualifies as a significant doubled die variety even though it is not a large part of the design that was affected. Minor Doubled Die Varieties: These varieties tend to have very close spreads to the doubling and/or somewhat limited amounts of doubling. Stronger magnification than 10X is often needed to pick up the doubling on these varieties unless you have a well trained eye. The “die hard” doubled die collectors will seek these out, but many collectors will most likely not pursue adding them to their collections.

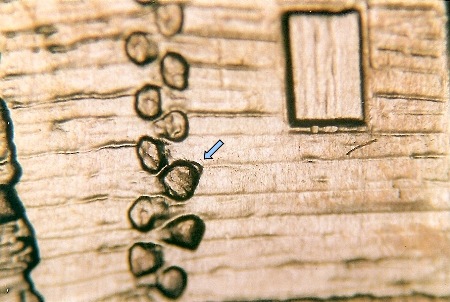

This is 1956 5¢ WDDR-034. Doubling shows as split serifs on the upper letters. A close spread can also be seen on the R and B of PLURIBUS. This one would be classified as a "minor" doubled die variety.

While readily visible, the doubling seen here on the underside of the thumb on 2009 1¢ FY WDDR-008 is considered to be a minor doubled die variety.

This is the Minnesota State quarter doubled die variety that we have listed as 2005-P 25¢ MN WDDR-021. The doubling on the lower right part of the target tree is considered to be a minor doubled die variety. Very Minor Doubled Die Varieties: Doubled dies in this category tend to show very little doubling. Often all that can be seen are some split serifs or some notched corners to some of the letters. Many of the Lincoln cent “doubled eyelid” varieties fall into this category as well. They may have relatively wide spreads, but show only a very small doubled image. Usually high magnification is required and only the hardiest of doubled die collectors will go after these.

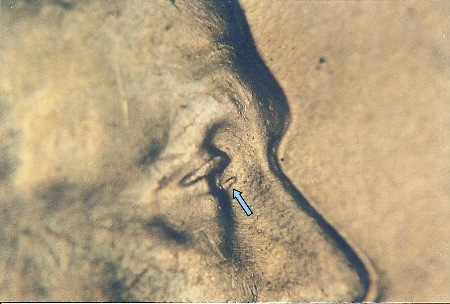

Here we see a "doubled eyelid" variety on 1944-S 1¢ WDDO-020. It is the only doubling on the obverse of the cent making it a "very minor" doubled die variety.

The small amount of doubling on the reverse of 2009 1¢ EC WDDR-009 puts this doubled die in the very minor category.

The small amount of doubling at the joint of the index finger puts this 2009 Formative Years 1¢ doubled die variety into the very minor doubled die category and values for it should reflect that ranking.

When it comes to the value of a doubled die variety, rarity is certainly a major factor in determining value and you need to keep in mind the fact that the doubling is on the die that is striking the coins. As long as that die is kept in use, it will continue to strike coins with that doubling. Some of the major and very significant doubled die varieties were caught by Mint coining press operators and removed from service. These would have very low mintages that would contribute to their value. However, most if not all of the minor and very minor doubled die varieties likely were not caught. In many cases even if they were detected, they were frequently ignored since the minor doubling was hardly noticeable and did not affect the production of the coins. The average die life for Lincoln cents is about one million coins so if a minor Lincoln cent doubled die variety went undetected or ignored because it was deemed too minor and unimportant, there most likely would be somewhere in the area of a million or more specimens available to collectors. One must be careful not to pay over inflated prices for these varieties or to charge over inflated prices for them. Just because it is a “doubled die” variety, it does not mean that it is scarce, rare, or valuable.

Doubled die varieties listed in the Wexler Doubled Die Files are listed with numbers such as 1955-D 1¢ WDDO-001. The first two items give the date, Mint, and the denomination. In this case we would be referring to a 1955 D-Mint cent. The W in WDDO refers to the fact that it is a listing in the Wexler Files. The DDO in WDDO indicates that it is an obverse doubled die variety. The 001 at the end of the notation indicates that it is the first doubled die variety reported for the obverse of the 1955-D Lincoln cents. The second obverse doubled die reported for the 1955-D Lincoln cents would be listed as 1955-D 1¢ WDDO-002. Doubled dies for the reverse of the 1955 Lincoln cents would be listed with numbers such as 1955 1¢ WDDR-001, 1955 1¢ WDDR-002, etc. Sometimes a “Pr” designation will be found in a doubled die listing such as 1955 1¢ Pr WDDO-003. This indicates that the doubled die variety was found on the obverse of a 1955 proof coin and it was the third obverse doubled die reported for the 1955 Lincoln cents. Likewise "SF" in a listing number will indicate that the coin has the Satin Finish found in the modern mint sets. For some special series issued by the Mint such as the Statehood Quarters, an additional notation in the listing number will give more information about the coin that the doubled die can be found on. In the case of the Statehood Quarters, the postal abbreviations for the states are used in the listing numbers. 2005-P 25¢ MN WDDO-001 indicates that it is Obverse Die #1 for the 2005-P Minnesota State quarters. In the Presidential Dollar series, the listings include the initials of the President being honored on that coin. A listing of 2008-P $1 MVB WDDR-001 indicates Reverse Die #1 for a 2008-P Martin Van Buren dollar.

If you have coins that you suspect are doubled dies and would like to find out if they are indeed genuine doubled die varieties, or if you know that they are doubled die varieties and would like to find out if they are listed in the Wexler Die Variety Files, you can send them for attribution using the guidelines here. Go To: | ||